Recently, I gave a presentation arguing that community ownership is key to understanding popular support in Germany for the Energiewende. On the next day of that event, however, Greenpeace’s Sven Teske told the same audience that he received considerable resistance from communities in the 1990s. Participants were totally confused.

Teske and I sat down together during a coffee break to see why we disagreed. It turned out we didn’t. I had given the example of Vauban, a neighborhood in Freiburg, Germany. In the early 1990s, citizens who wanted to build homes there petitioned the local government to get car-free side streets. When I give tours of the area, however, visitors often ask how city officials got people to accept not being able to park their cars in front of their homes – the expectation outside Germany obviously being that the Energiewende is project handed down from above by sustainability experts. In reality, German citizens have demanded that their government take action, and German democracy is, fortunately, responsive enough.

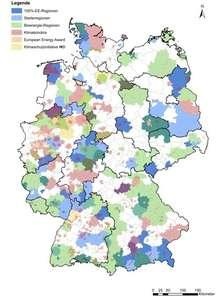

Teske was describing the same thing – local public officials resisting Greenpeace’s ideas in the 1990s. In the meantime, municipalities are on board; governmental officials have joined the citizens’ grassroots movement called the Energiewende, as the following map shows.

Around half of Germany is now consists of campaigns for clean energy of one kind or another, so public officials have clearly picked up the baton. The difference between municipal and community is thus shrinking, but it still exists, especially when it comes to conventional energy.

Take coal power. On the Twitter, the head of British climate NGO Sandbag recently asked me if it is okay to burn coal as long as communities do it. The question makes no sense to me if we speak of communities, but it does if we say “municipalities.” Municipal utilities do own coal plants and gas turbines. The town of Freiburg, which calls itself Green City, only recently switched from coal to gas in its district heat supply because of the obvious contradiction.

German journalist Jörg Staude recently made the distinction between community and municipal even clearer in his article entitled (in German) “Undemocratic lignite.” As he puts it, no community wants lignite, which is only cheap when it is huge and devours entire communities. And the bigger a project is, the less it is in line with “the ideal of a humane, emancipating, self-determined society.”

The distinction is all the more pertinent today under Social Democrat Economic Minister Sigmar Gabriel, who is defending firms and workers in the coal sector. Communities want to make their own energy, and that generally means renewables. Move up the political ladder, however, and you increasingly encounter support for big business, even at the expense of democratic will – with some communities even being sacrificed in the name of eminent domain.

Municipal governments are somewhere in the middle. They have not always been supportive of their citizens going renewable, but they increasingly are. They also remain closely associated with the conventional energy sources, which until a few decades ago were the only option even at the local level.

A similar distinction needs to be made in the US, incidentally. As my colleague John Farrell recently explained, the US has rural electricity cooperatives, and co-op is the translation for Bürgerenergie, but US co-ops are not necessarily "champions of local clean power."

(Craig Morris / @PPchef)